How natural is your database schema?

This post is about our project SNAILS and paper: SNAILS: Schema Naming Assessments for Improved LLM-based SQL Inference, to be published at ACM SIGMOD 2025. You can access the project artifacts and code on our GitHub repository and learn more about our research in our technical report.

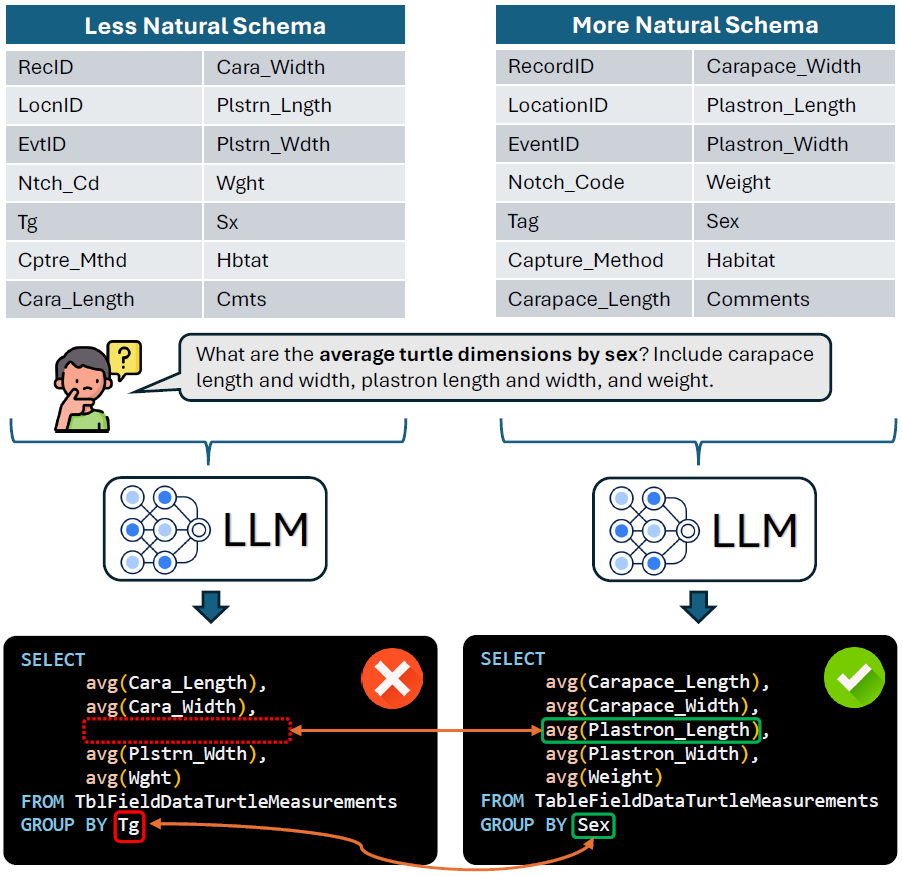

LLMs have revolutionized natural language interfaces with databases (NLIDB), and there are many interesting and effective NL-to-SQL methods described in various papers and evaluated on NL-to-SQL-focused benchmarks including Spider and BIRD. But what, until now, was somewhat lacking was a deep examination of schema identifier (table and column names) naturalness, and how it affects NL-to-SQL performance.

Enter our SNAILS project! With SNAILS, we posit that the way a database schema is named will have a major effect on the quality of an LLM-based NLI integration with real world databases. Specifically, more naturally-named schemas will perform better than less natural schemas, and (spoiler alert!) the findings published in our SIGMOD 2025 paper show just that–there is a statistically significant correlation between schema naturalness and NL-to-SQL performance.

Isn’t it obvious?

Intuitively, more naturally-named schemas should perform better, but from a scientific standpoint, it helps to know how we can quantify the impact and how it varies across LLMs, queries, and databases. Once we know (and knowing is half the battle), then we can take definitive action toward measurable improvements in schema naturalness that we know will improve the chances of a successful NLI integration with our databases.

What is naturalness, exactly?

Although that can seem like a philosophical question, in this first work on this topic, we take a first step by concretely defining naturalness with a categorical approach with three distinct levels: Regular, Low, and Least.

- Regular: The identifier contains complete English words with no abbreviations or acronyms, or contains only acronyms in common usage (e.g., ID or GPS).

- Low: The identifier contains abbreviated English words and less common acronyms that are usually recognizable by non-domain experts (e.g., UTM or CPI). The meaning of the identifier can be inferred without consulting external documentation.

- Least: The identifier’s meaning cannot be inferred by non-experts due to indecipherable acronyms or abbreviations, and external metadata or other documentation must be consulted in order to determine its purpose.

One of the databases in the SNAILS collection is a training database from the SAP Business One ERP, which contains almost 500 tables and over 5,000 columns. Here are two examples, one table and one column, of the identifiers as they exist in the database (i.e., Native), and the modified identifiers in the SNAILS dataset.

| Identifier Type | Native | Regular Naturalness | Low Naturalness | Least Naturalness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Column | AcqAcct | AcquisitionTaxAccount | AcqAcct | AcAct |

| Table | ADOC | invoice_history | inv_hist | ADOC |

We won’t bore you with a myriad of examples, but if you’d like to peruse the SNAILS project artifacts, you can find thousands more examples of identifiers and their naturalness levels.

What is SNAILS?

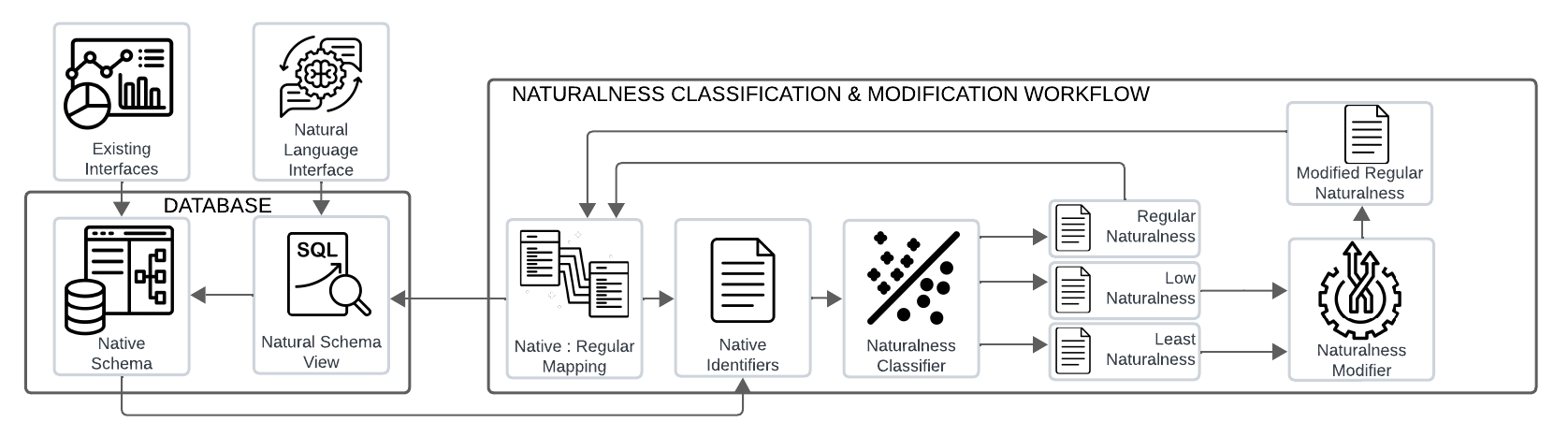

SNAILS is a set of NL-to-SQL-related artifacts designed to explore the effects of schema naming on LLM-based NL-to-SQL performance. It includes a set of real-world databases and associated natural language (NL) : SQL gold query pairs, human-labeled data containing naturalness classifications the tables and columns in the database collection, a model and method for ML-based naturalness classification, and prompting strategies for improving schema identifier naturalness.

It started with a question

The SNAILS project started with a simple question: How does a database’s schema design affect the performance of NL-to-SQL? There are several different aspects of schema design, including normalization levels, dependency constraints, element naming, and more. For this first project, we decided to focus on schema naming, which quickly led us toward the concept of naturalness.

It revealed a need

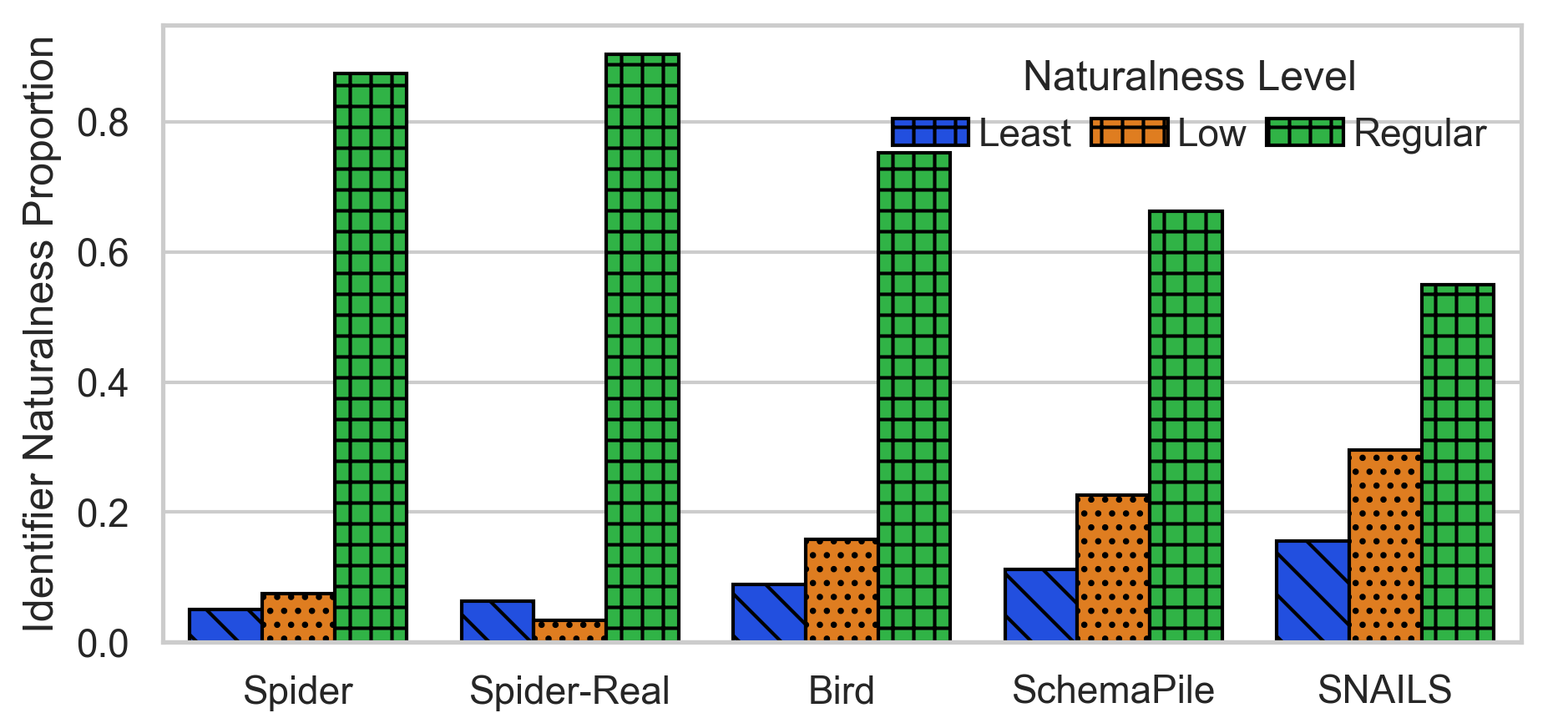

The chart above shows the frequency of identifiers of different naturalness levels across benchmarks and schema collections. We identified a need for a new set of real-world databases that contained a variety of different naming patterns. This is because existing benchmarks such as Spider and Bird, while excellent for their intended purposes, tended to contain more naturally-named schemas than we encountered when we began analyzing naming patterns in real world databases and schema repositories such as Schema Pile.

It inspired a set of artifacts

In response to the need for a schema naming-focused dataset, we created several artifacts that we used to perform our analysis:

-

A collection of 9 real-world database instances sourced from multiple domains: we gathered these publicly-available datasets from US Federal and local government sources as well as from the SAP Business One ERP training schema.

-

A dataset of over 17,000 table and column names labeled with their naturalness levels. We accomplished this using human labelling for an initial subset, and then weak human supervision using an ML-based naturalness classifier.

-

An ML-based naturalness classifier trained to classify the naturalness of an identifier into Regular, Low, or Least naturalness categories.

-

A dataset of over 17,000 naturalness-modified identifiers that map to the native identifiers in the labeled dataset above. This allows us to create alternate virtual schemas for each of the nine databases in the SNAILS collection.

-

Naturalness modifiers for both increasing and decreasing identifier naturalness. Decreasing naturalness happens using few show LLM prompting. Increasing naturalness is more complex, and we created a RAG-based method that extracts identifier definitions from provided database metadata and, with the help of an command line interaction with a human, creates a few shot prompt tailored to the target schema.

-

503 NLQ - Gold SQL Pairs for evaluating naturalness effects. We created 503 queries over the native databases, which we then also modified to query over each of the 3 naturalness-modified databases schemas for the 9 SNAILS database schemas.

It showed us how naturalness affects NL-to-SQL performance

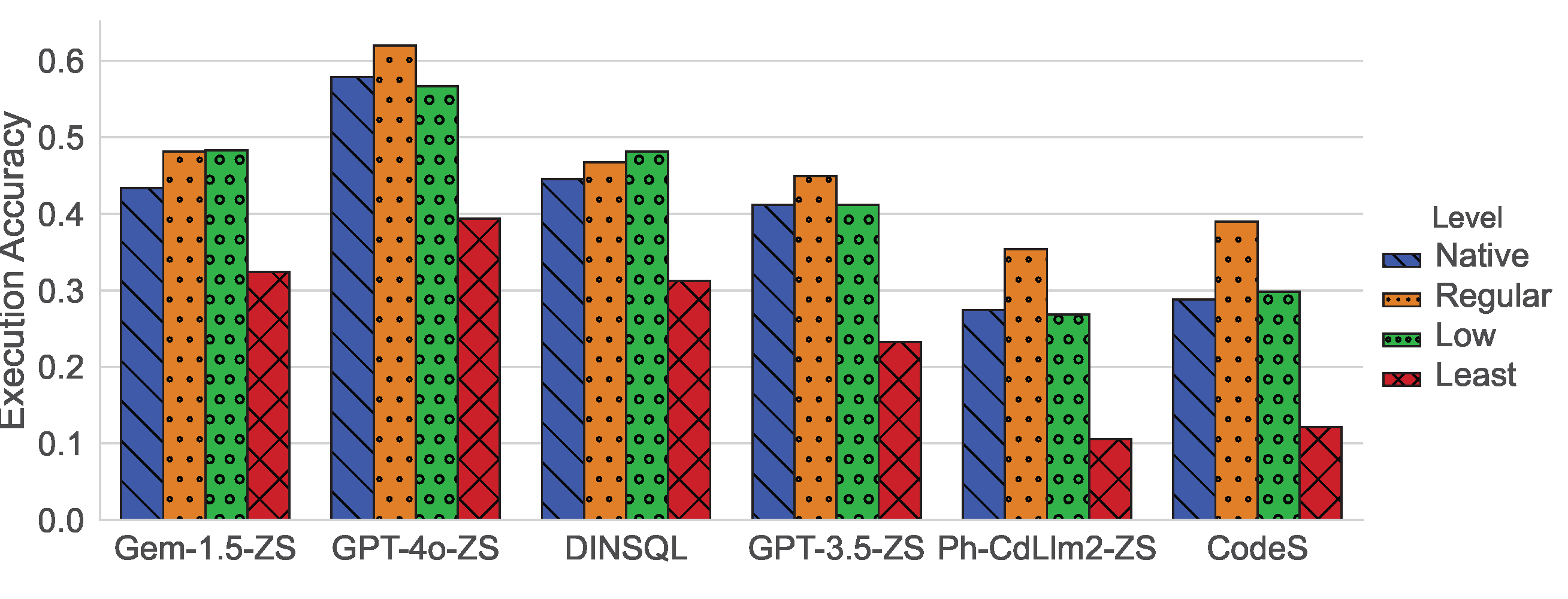

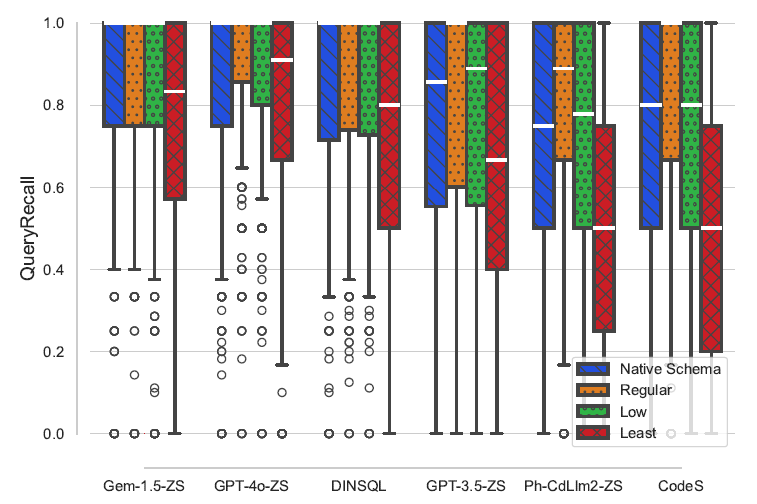

We ran several LLMs including GPT-4o, GPT 3.5 Turbo, Gemini 1.5 Pro, Phind CodeLlama (a finetuned version of Code Llama), and two more complex NL-to-SQL workflows: CodeS (StarCoder finetuned for NL-to-SQL), and DinSQL. We also created alternate virtual schemas of different naturalness levels for each database. The individual bars in both of the charts below display performance for each database naturalness version.

The the typical metric for most NL-to-SQL benchmarks is Execution Accuracy, and so we also use it as one of our evaluation methods. The chart above shows execution accuracy for each LLM or NL-to-SQL method over each schema naturalness level.

The chart above shows QueryRecall, which is the number of database identifiers in an LLM-generated SQL query over the number present in the corresponding gold SQL query. In our project, we created alternate virtual schemas of different naturalness levels for each database. The individual bars in the chart display the QueryRecall performance for each database naturalness version.

As you can see from these charts, the magnitude of the effect that naturalness has on schema linking varies by LLM, with more recent and more capable LLMs showing less sensitivity and smaller LLMs showing more sensitivity to naturalness. Despite a higher tolerance for lower naturalness in some models, we can still observe decreasing performance as naturalness decreases, particularly for our Least natural schemas.

It offers more research opportunities

As we discussed above, using the SNAILS artifacts we found that naturalness has an effect on NL-to-SQL performance. In our first work, we limited our scope to three naturalness categories. In the future, we imagine the possibility of a more fine-grained naturalness descriptor (either continuous or categorical). Additionally, we wonder if similar effects can be measured relating to other schema design patterns such as normalization, dependency constraints, table counts, column counts, etc.

The SNAILS artifacts also offers opportunities for researchers focused on designing NL-to-SQL systems to stress test the schema linking capability of their implementations against the SNAILS dataset. This may expose other methods for improved schema linking beyond our natural view construct that we discuss next.

The idea of naturalness and its effects on NL-to-SQL translation poses new questions in the intersection of NLP and database schema design (e.g., embeddings, latent space, tokenization, etc.) that the SNAILS artifacts can help answer.

How can we make our databases more natural?

Given this new knowledge, how can practitioners use it to make their NL-to-SQL tools better? In our technical report, we break the action options into two categories: those for new databases, and those for already existing (i.e., legacy) databases.

- New Databases

- Name tables and columns using the criteria of the Regular naturalness definition.

- Avoid obscure acronyms and abbreviations.

- Existing Databases

- Use the SNAILS classifier to gauge schema naturalness.

- Where needed, improve Low and Least naturalness identifiers using the SNAILS naturalness modifiers.

- Map native identifiers to natural identifiers and represent them as more natural SQL views or using a middleware approach.