Deep Learning in Data Systems: How?

This post is about our project Cerebro and paper: Distributed Deep Learning on Data Systems: A Comparative Analysis of Approaches. Please check the home page at here.

For decades, data systems have been central to data analytics, and there have been enormous efforts to integrate machine learning into DBMS. This paradigm of “In-DBMS ML” (or “In-data system ML”) has waxed and waned over the last 20 years. In the past decade, there has been this revolution of deep learning, and it’s been so popular and widely adopted. In this context, the increasingly asked question is how we can enable seamless support for deep learning over DB-resident data.

Why not just export and go?

Why do we care about this topic? Why don’t we just export the data to a data lake and run machine learning there?

First, because in-DBMS ML provides a familiar SQL interface to the DB users and business analysts. Second is the ease of provenance; this has always been important but recently got a renewed urgency due to regulations such as GDPR and CCPA, and DBMS already provides good support for governance and provenance. Last but not least is the mature distributed execution engine that a DBMS offers; we heard that SOTA deep learning tools are often criticized for being difficult to set up; DBMSes have the potential here to bridge the gap.

After all, why do you need to migrate your data to some other platform/system when your RDBMS can offer so much but just lacks that much-needed deep learning support?

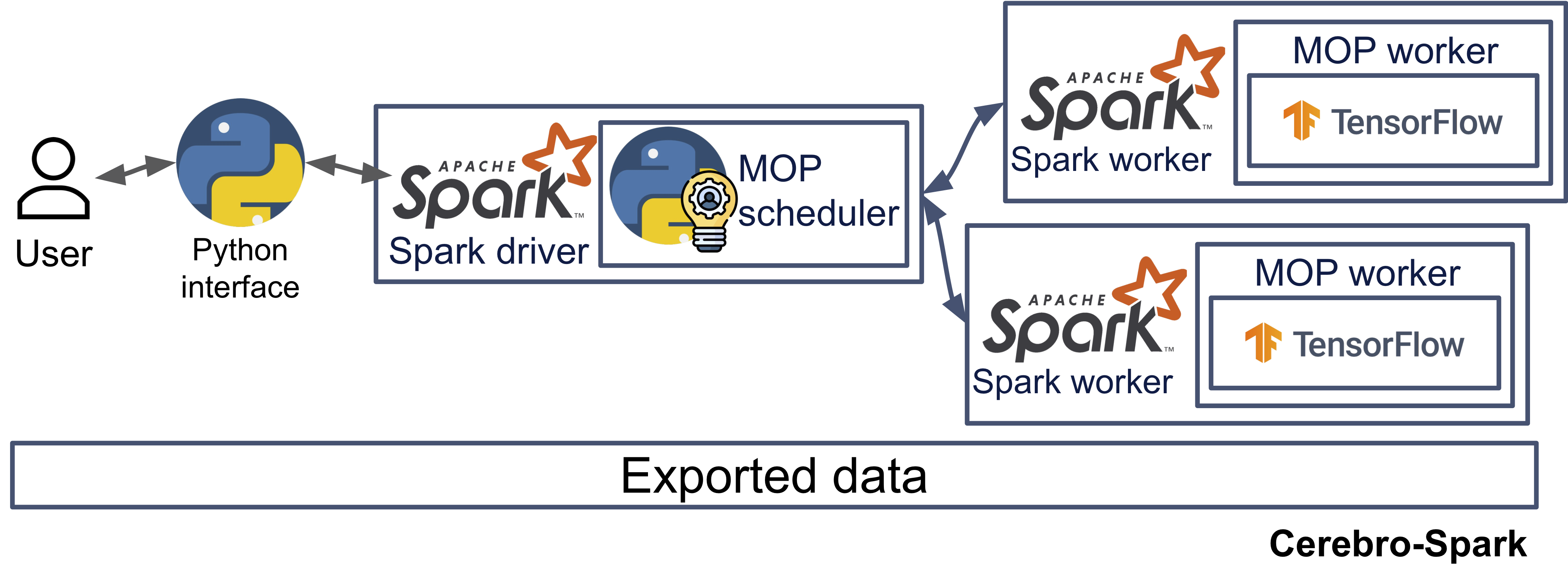

This when our work comes into the picture, we do not want to reinvent the wheel by building a deep-learning-specialized DBMS or competing with Google or Facebook to have our own deep learning framework. We try to find a solution by integrating our distributed DL training system, Cerebro, into (ideally any) existing RDBMS, without touching its codebase.

Wait, what about DL systems other than Cerebro?

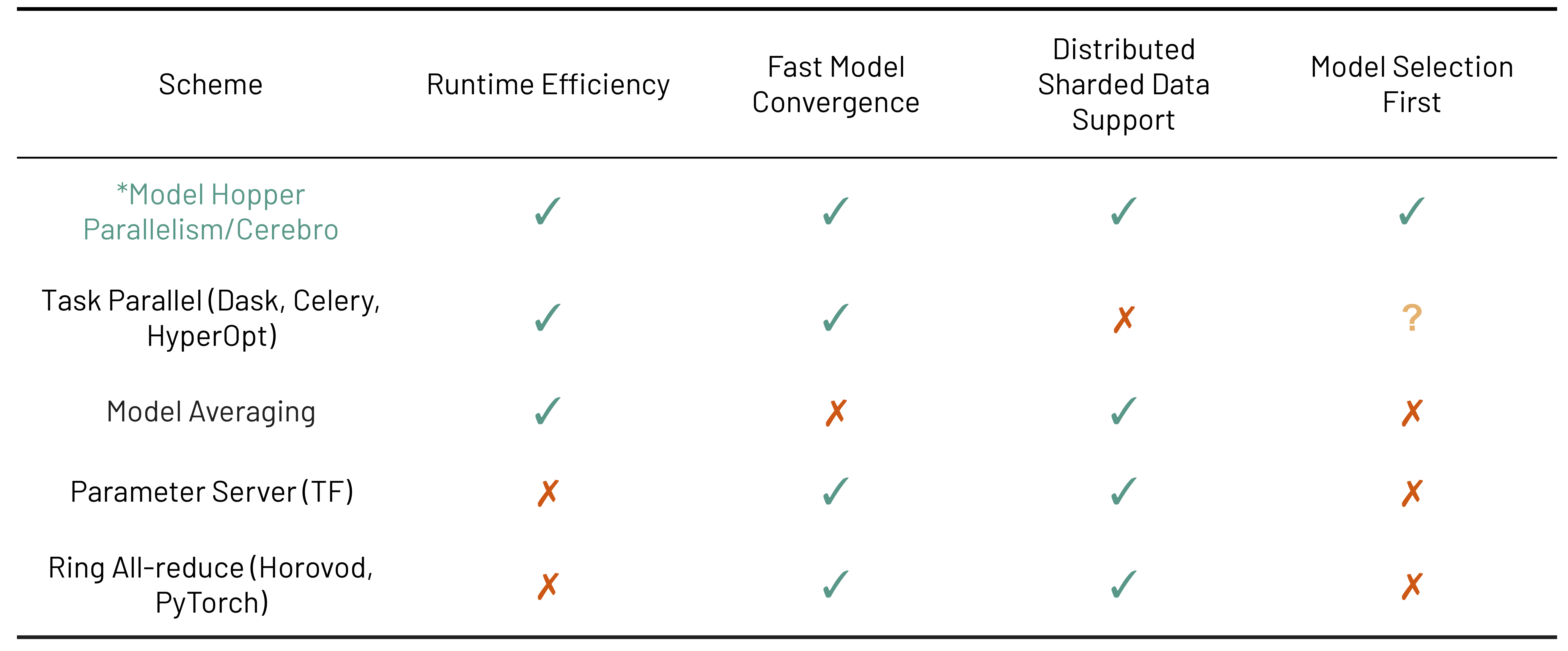

It’s definitely not (only) because Cerebro is our own work. As a matter of fact, in addition to Cerebro and its training scheme Model Hopper Parallelism (MOP), there exists plenty of DL training and model selection systems such as the Parameter Server, model averaging, task-parallel, and the ring-allreduce-based systems. Each of them falls short on some end, and we genuinely believe Cerebro is the better choice for distributed in-DBMS deep learning.

In the paper, we compared against Pytorch Distributed Data-Parallel and it turns out to be 3x slower than Cerebro. We also played with Hyperopt and Cerebro can match its performance and have the benefit of better data scalability.

To summarize: model averaging has convergence issue, parameter server/ring-all reduce is bottlenecked. Task-parallel does not work with MPP DBMS. MOP is generally more efficient and converges fast.

To see why Cerebro has such a magical performance, I highly recommend you to read our previous paper and blog.

The four approaches of integration

We imagined four canonical paths that can be taken to integrate Cerebro into DBMS, ranging from tight to none integration with DBMS. Note these approaches are not limited to Cerebro/MOP; we can also use them to implement other deep learning training schemes.

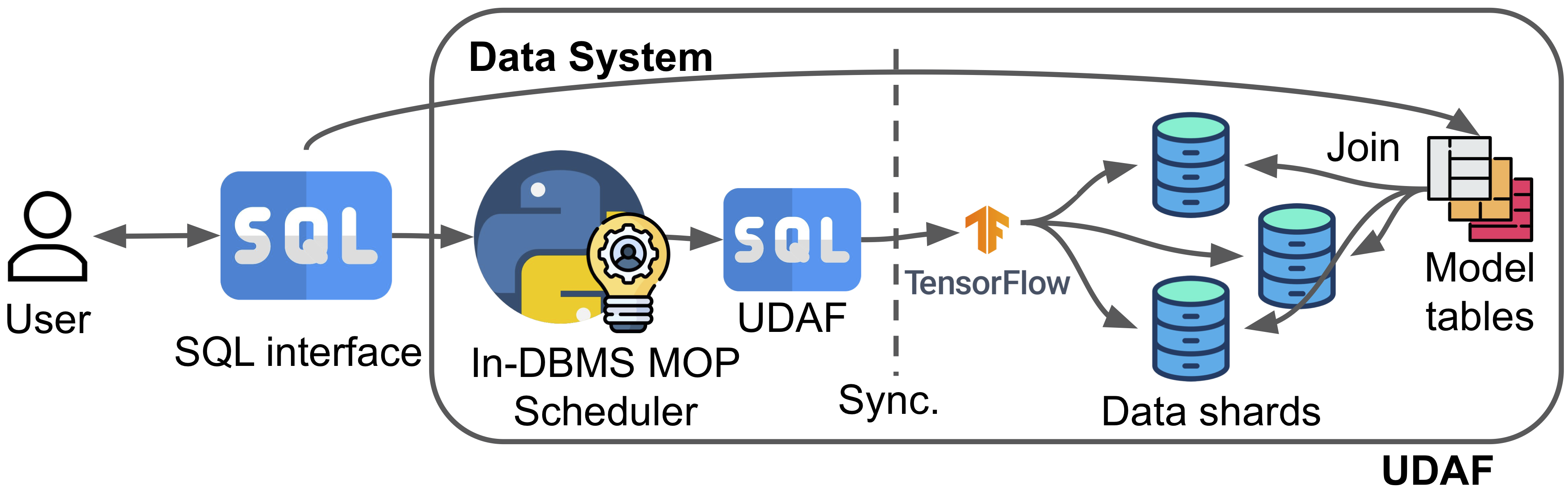

Fully in-DBMS (UDAF)

The first approach is through the User Defined Aggregate Function (UDAF) extension of the DBMS. We basically translate the deep learning training tasks into UDAFs, which then invoke TensorFlow for DL. The pros are ease of governance, and it fits in existing design patterns such as MADlib; in fact, this approach has been adopted by it. The cons are overheads accessing data from the DBMS to python and TensorFlow. And there are synchronization barriers imposed by the DBMS, but MOP is essentially an asynchronous method, so we had to force MOP to work in the sync mode; this may hinder efficiency when the workload is imbalanced.

Pros:

- Ease of governance.

- Fits in existing design patterns such as MADlib’s

Cons:

- Overheads when accessing dataSync.

- Sync barrier imposed by the DBMS

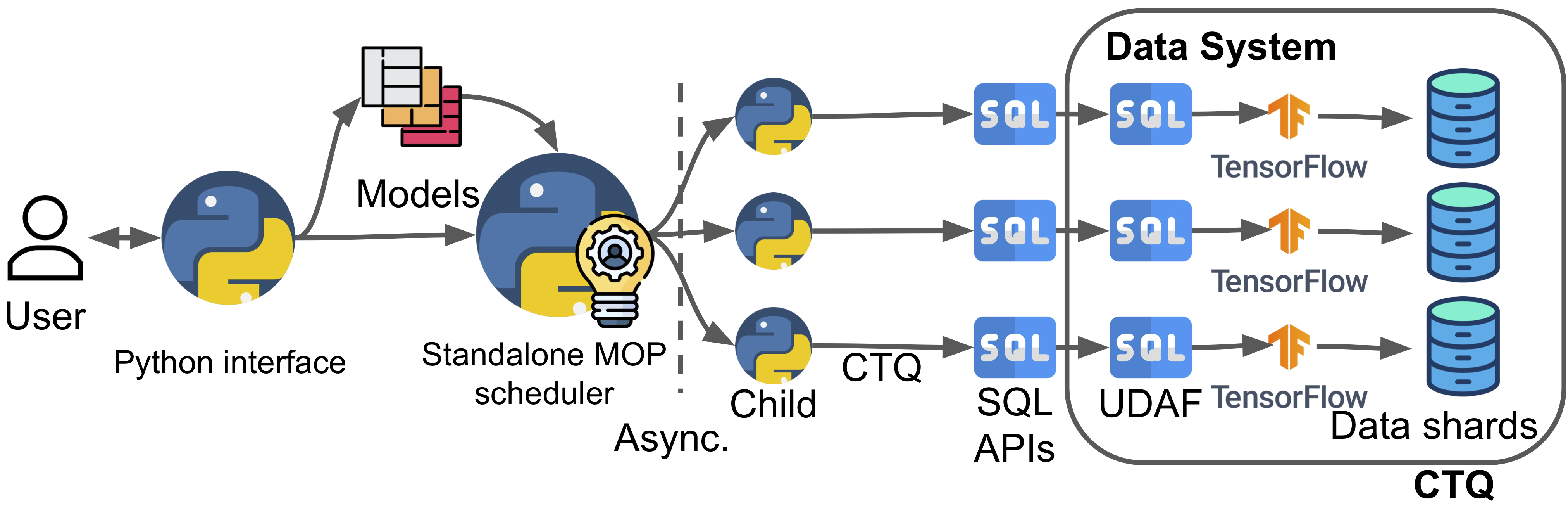

Partially in-DBMS (CTQ)

The next approach is what we call Concurrent Targeted Queries (CTQ). It’s mainly designed to bypass the sync barriers; we dissect the training query into multiple queries with some tricks so that the query planner can send a targeted plan to each node. And they can return asynchronously. We then put them on a job queue and concurrently run them, collect the results, and stitch them together later. Hooray, asynchrony! Cons are still the data accessing overhead, and this may potentially violate some design code.

Pros:

- No barrier and better runtime efficiency

Cons:

- Overheads when accessing data

- Potential design anti-patterns as we bypassed the query planner and realized parallelism by ourselves

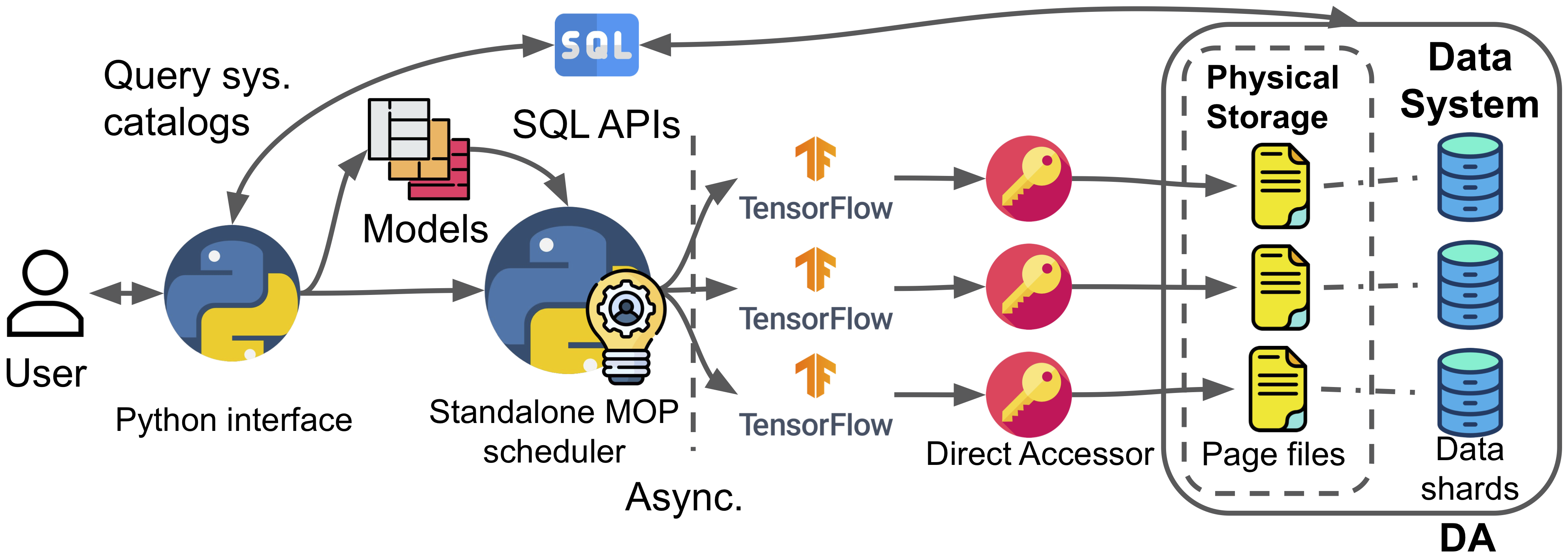

In-DB but not in-DBMS (DA)

We encountered many troubles due to the proprietary data storage formats (called pagefiles) that nowadays RDBMSes use. This kind of design largely denies access from anywhere except the DBMS’s internal methods. However, going through the entire query stack of the DBMS and shipping it to the DL tools drastically bottlenecks the performance. Also, for DL workloads, we need nothing more than a simple table scan.

In this work, we devised a Direct Access (DA) trick to read the pagefiles and cache them in memory ourselves. Then technically, the data still remains in the DB, but DBMS does not participate in the process.

The landscape is quickly changing though, the new Lakehouse architecture already starts to promote the use of open file formats like Parquet so that the DBMS and DL tools can finally live in harmony without our DA trick.

Pros:

- Offers high efficiency

Cons:

- Specific to the DBMS’s physical file format

- Poor portability

Fully out-of-DBMS (Export)

AKA: I am gonna export my data anyway! Well, congratulations, you picked the easiest route; we have a Cerebro-Spark system built to offer the best efficiency and zero DBMS guaranteed. Pros:

- Offers high efficiency

Cons:

- Loss in the ease of governance

Which approach of integration to choose then?

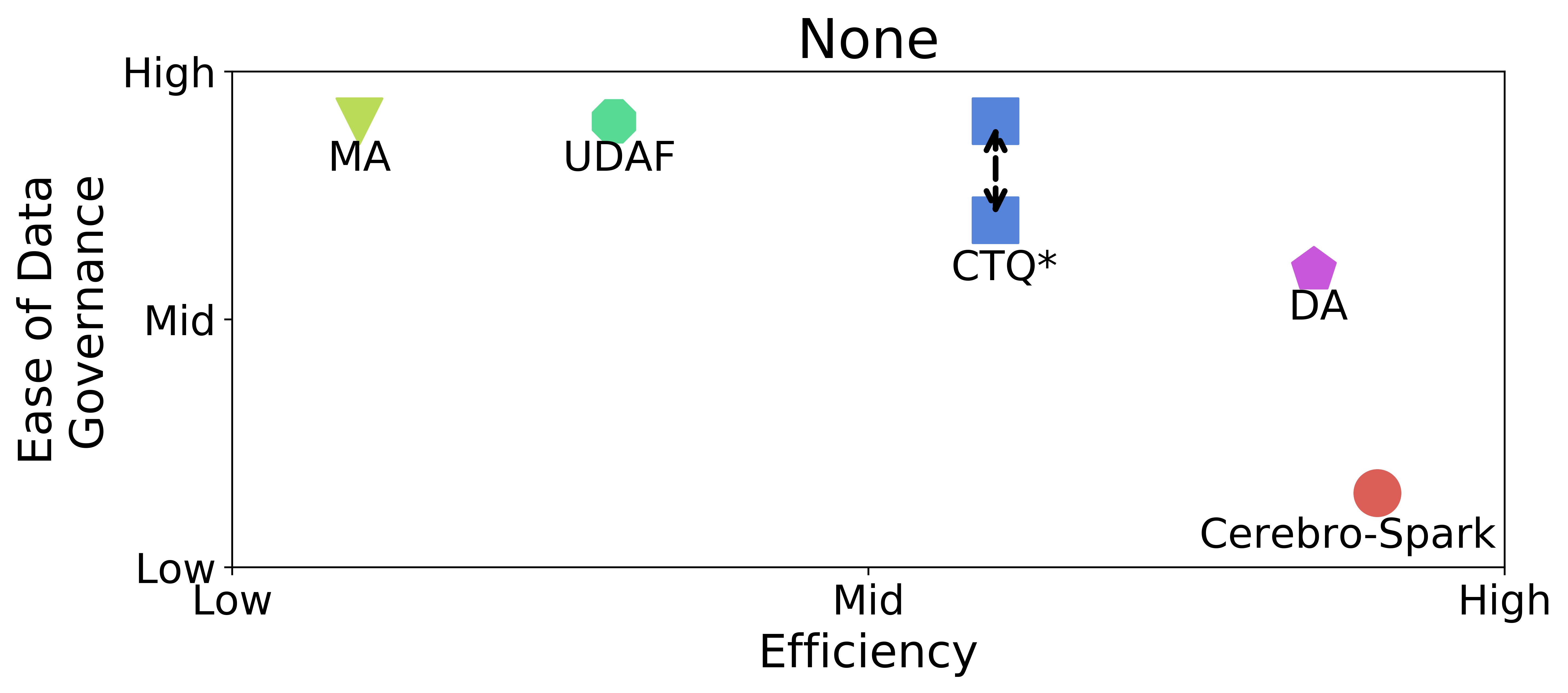

Well, it all depends. Overall, the in-DBMS approaches of UDAF and CTQ may provide better ease of governance, while DA and Cerebro-Spark offer better efficiency. Furthermore, CTQ provides asynchronous scheduling over UDAF, which leads to better efficiency for heterogeneous workloads but sacrifices some governance. DA and Cerebro-Spark provide the same efficiency level. DA, being more challenging to implement and less portable, can avoid data exports that Cerebro-Spark requires.

In the paper, we evaluated them on 6 axes of comparison; here, I only show the two most important axes, the ease of governance and efficiency. There are many more tradeoffs between these axes.

Takeaways

- Cerebro/MOP is a good option for in-DBMS deep learning, better than task-parallel, model averaging, and ring-allreduce

- It’s possible to integrate Cerebro/MOP into an existing DBMS without modifying the DBMS’s code

- There are four plausible approaches of integration and we evaluated them thoroughly to compare the pros and cons